By Joe Magee and Chris Uttley

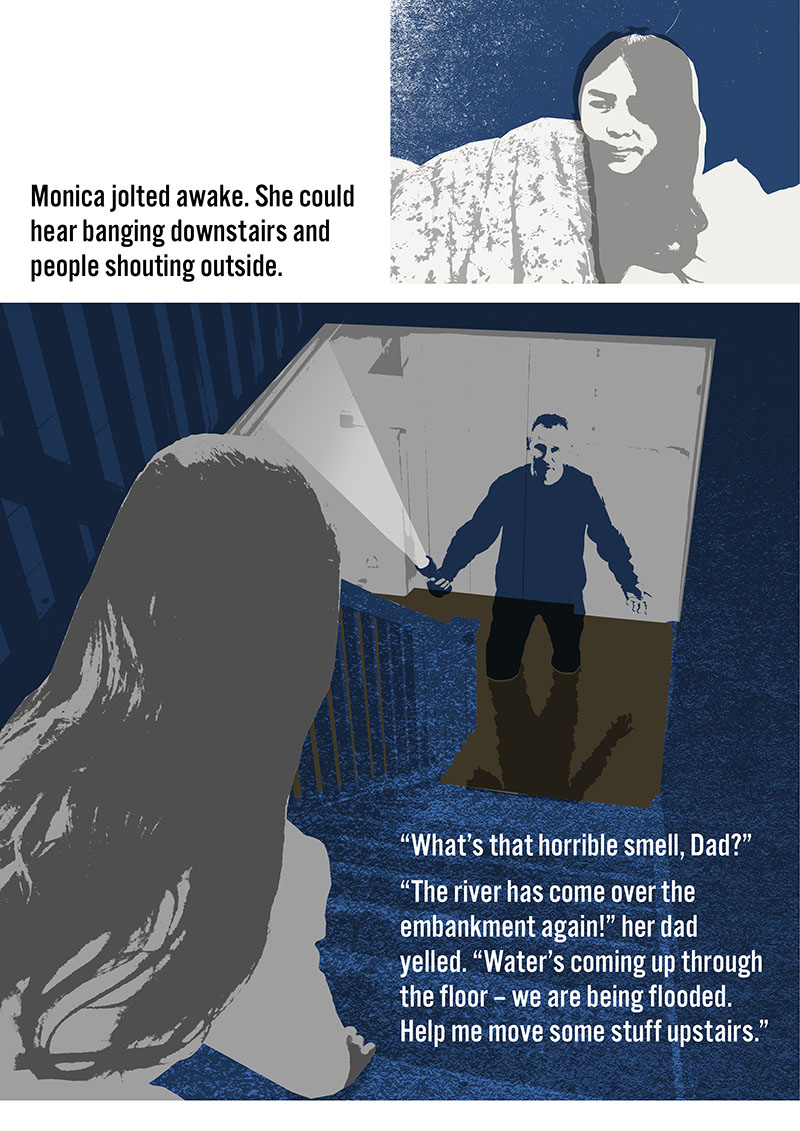

“What’s that horrible smell, Dad?”

“The river has come over the embankment again!” her dad yelled, “Water’s coming up through the floor – we are being flooded. Help me move some stuff upstairs.”

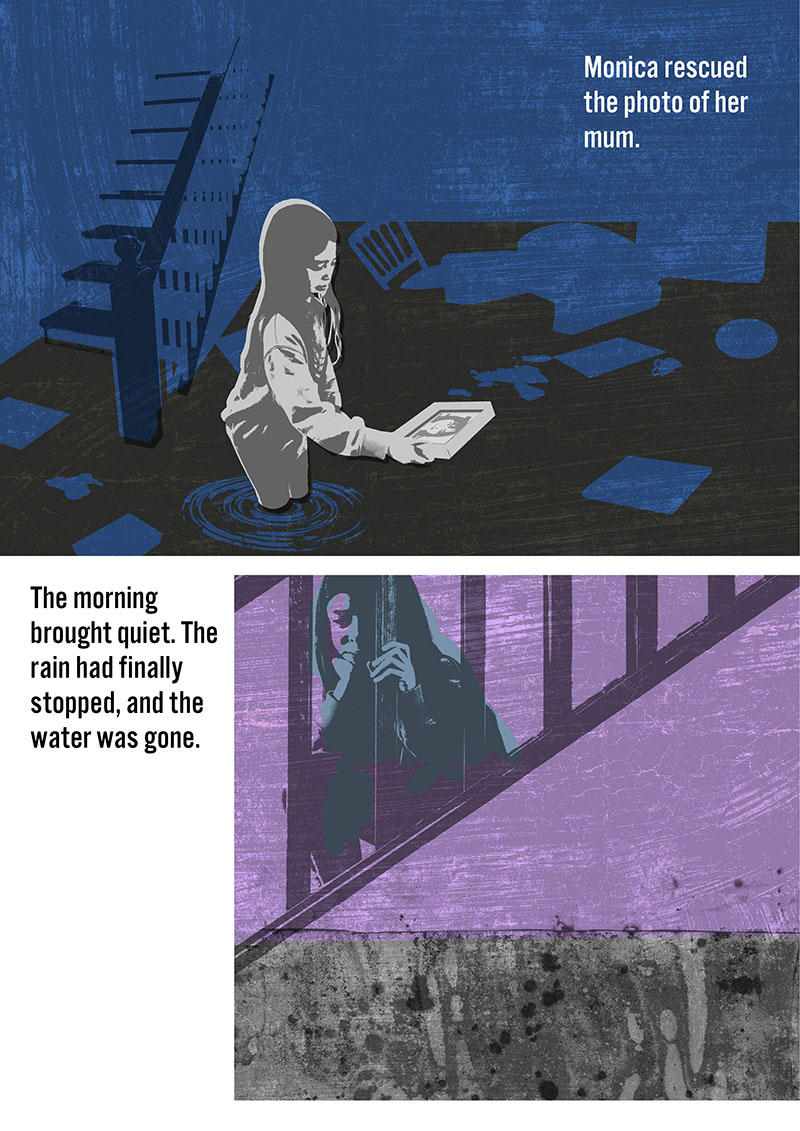

The morning brought quiet. The rain had finally stopped, and the water was gone.

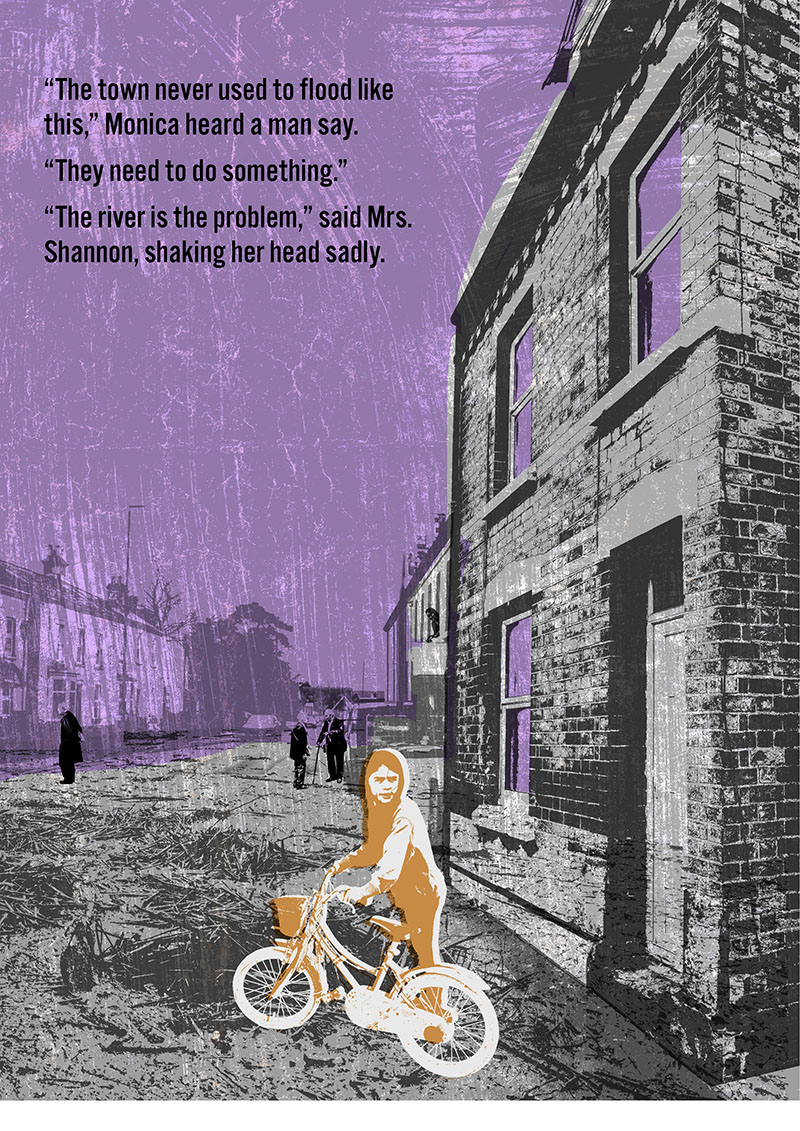

“They need to do something.”

“The river is the problem,” said Mrs. Shannon, shaking her head sadly.

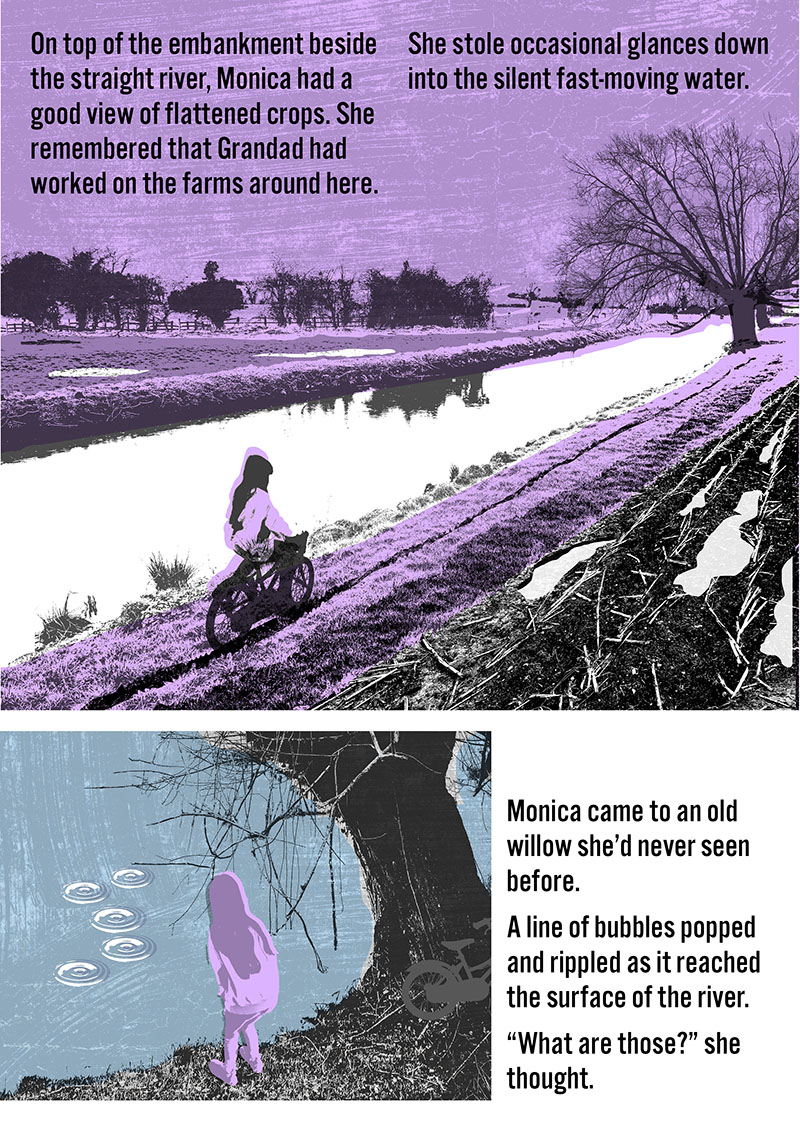

She stole occasional glances down into the silent fast-moving water.

Monica came to an old willow she’d never seen before.

A line of bubbles popped and rippled as it reached the surface of the river. “What are those?” she thought.

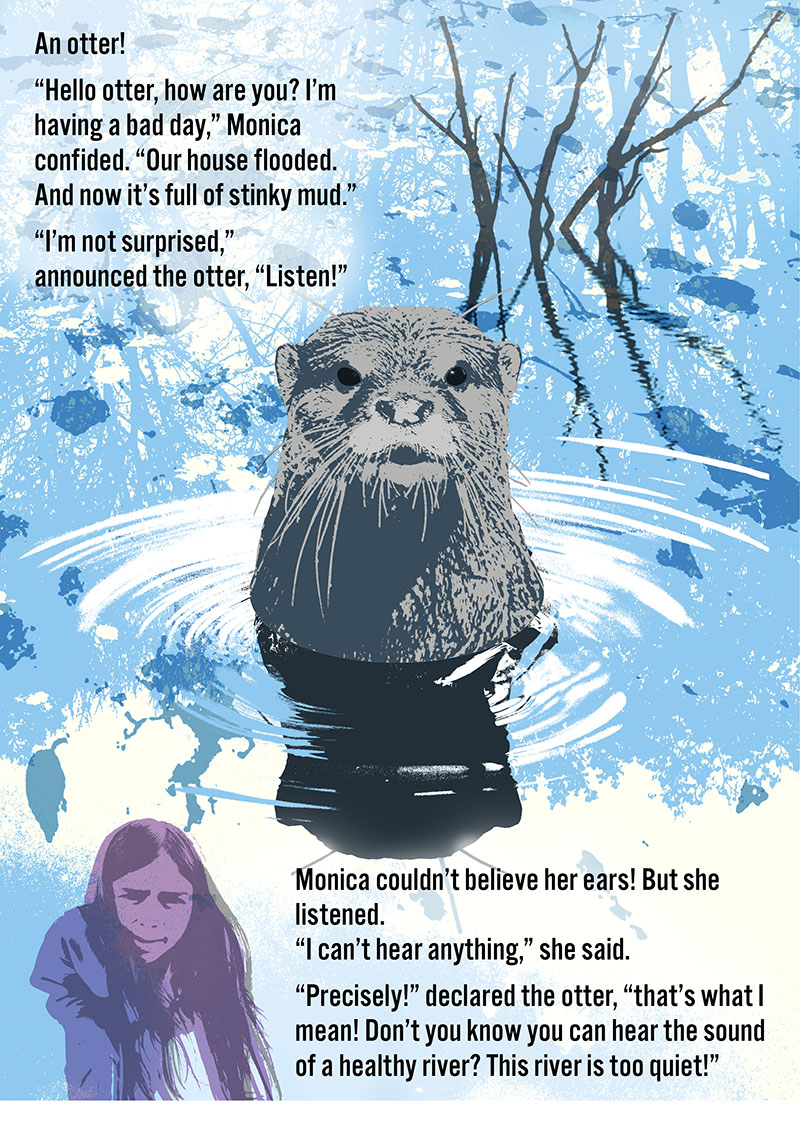

“Hello otter, how are you? I’m having a bad day,” Monica confided. “Our house flooded. And now it’s full of stinky mud.”

“I’m not surprised,” announced the otter, “Listen!”

Monica couldn’t believe her ears! But she listened. “I can’t hear anything,” she said. “Precisely!” declared the otter, “that’s what I mean! Don’t you know you can hear the sound of a healthy river? This river is too quiet!”

“Monica,” she replied. “But what do you mean, this river is too quiet?

“This,” said Lu, “isn’t how rivers are supposed to be. This river used to wriggle, splash, whistle, buzz, and hum through these fields. It used to sing with life.”

“But – how could a river make all those sounds?” she asked.

My tree could answer your questions” said Finn disappearing through a crack in the old willow. “Follow me!”

She hesitated for a moment before deciding to follow Finn into the willow.

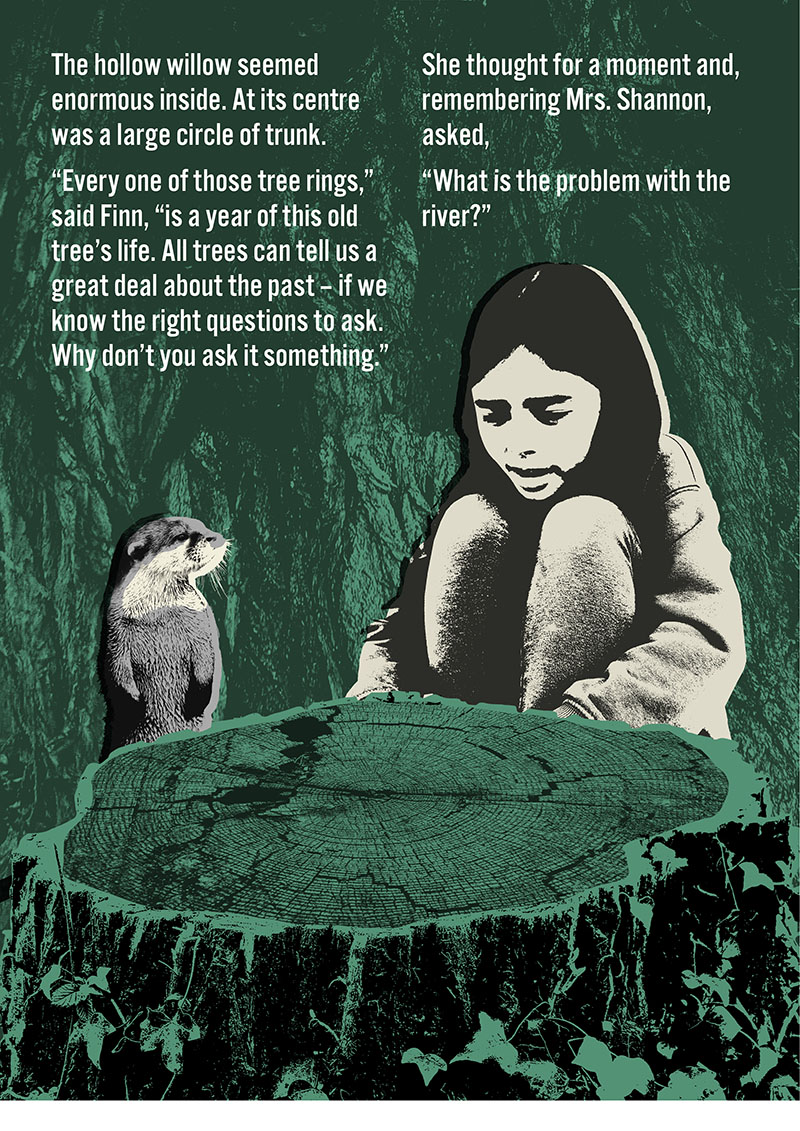

“Every one of those tree rings,” said Finn, “is a year of this old tree’s life. All trees can tell us a great deal about the past – if we know the right questions to ask. Why don’t you ask it something.”

She thought for a moment and, remembering Mrs. Shannon, asked,

“What is the problem with the river?”

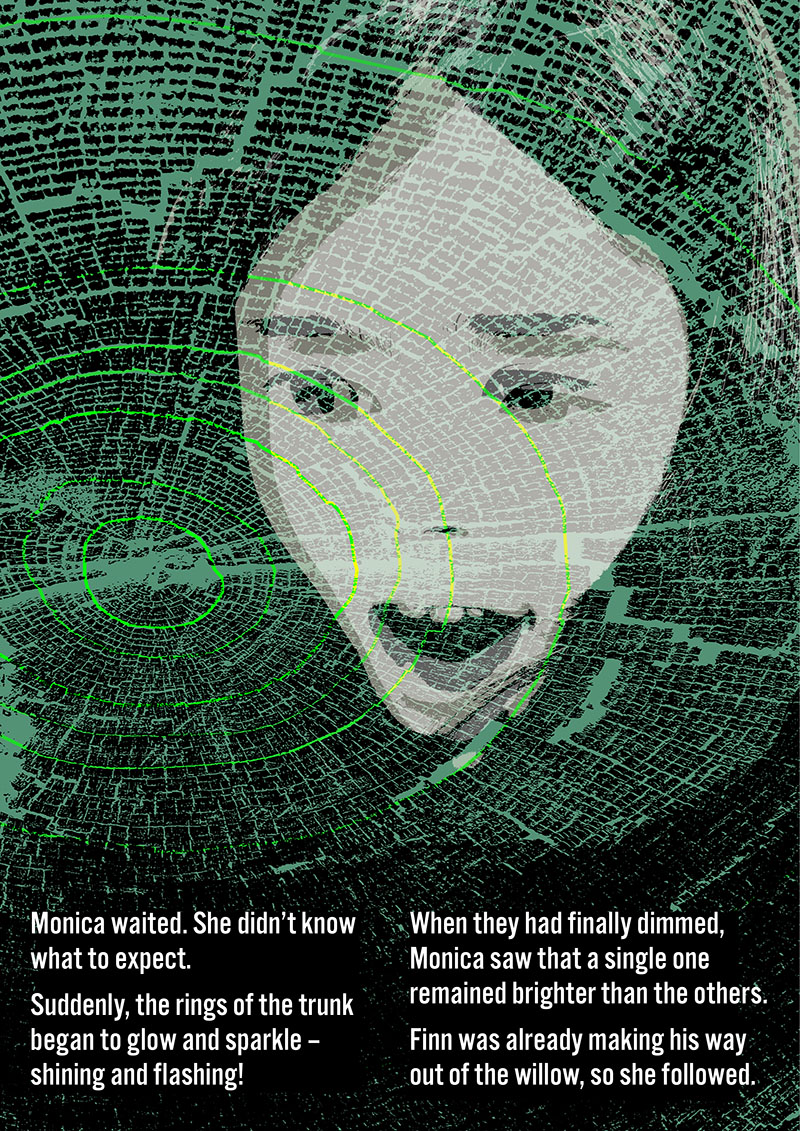

Suddenly, the rings of the trunk began to glow and sparkle – shining and flashing!

When they had finally dimmed, Monica saw that a single one remained brighter than the others.

Finn was already making his way out of the willow, so she followed.

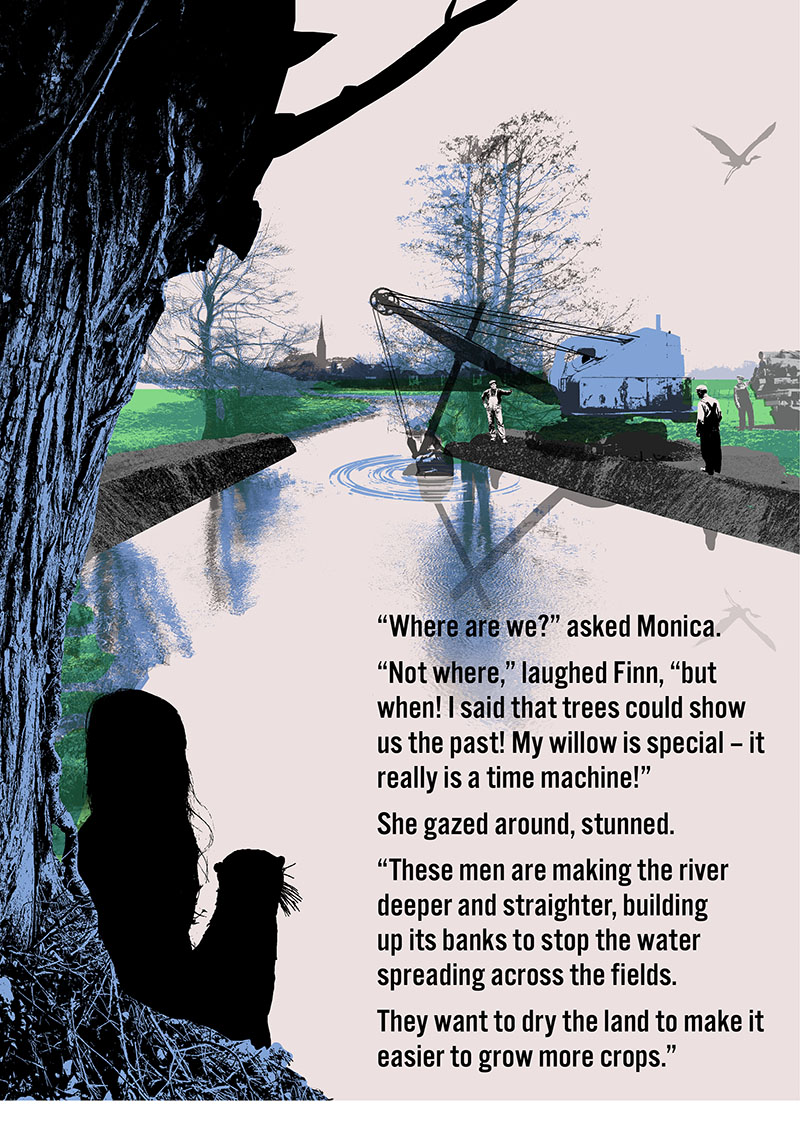

“Not where,” laughed Finn, “but when! I said that trees could show us the past! My willow is special – it really is a time machine!”

She gazed around, stunned. “These men are making the river deeper and straighter, building up its banks to stop the water spreading across the fields.

They want to dry the land to make it easier to grow more crops.”

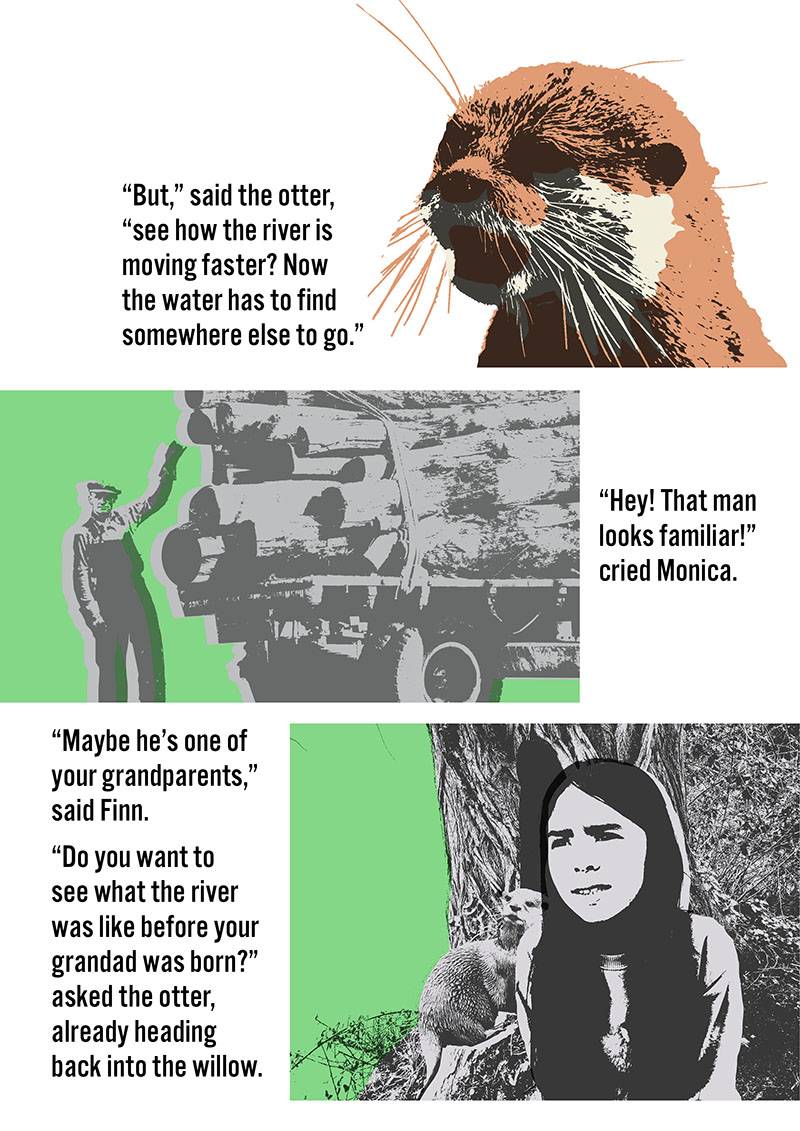

“Hey! That man looks familiar!” cried Monica.

“Maybe he’s one of your grandparents,” said Finn.

“Do you want to see what the river was like before your grandad was born?” asked the otter, already heading back into the willow.

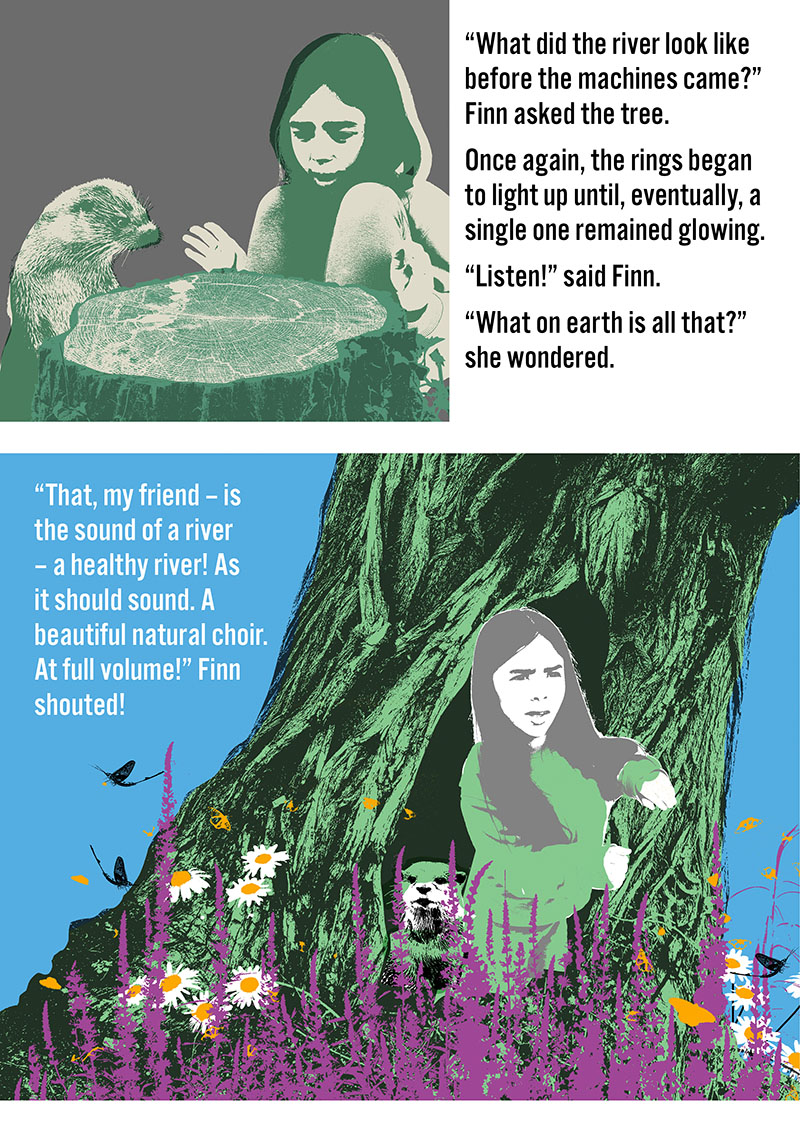

Once again, the rings began to light up until, eventually, a single one remained glowing.

“Listen!” said Finn.

“What on earth is all that?” she wondered.

“That, my friend – is the sound of a river – a healthy river! As it should sound. A beautiful natural choir. At full volume!” Finn shouted!

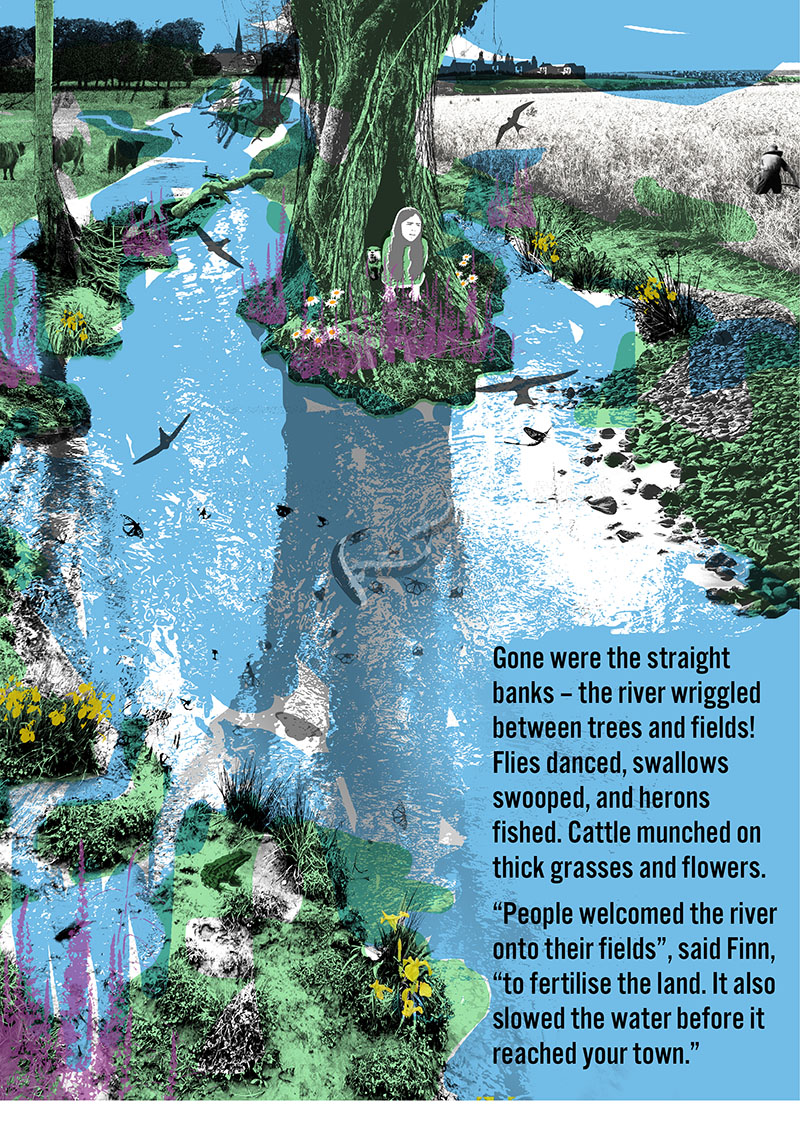

“People welcomed the river onto their fields”, said Finn, “to fertilise the land. It also slowed the water before it reached your town.”

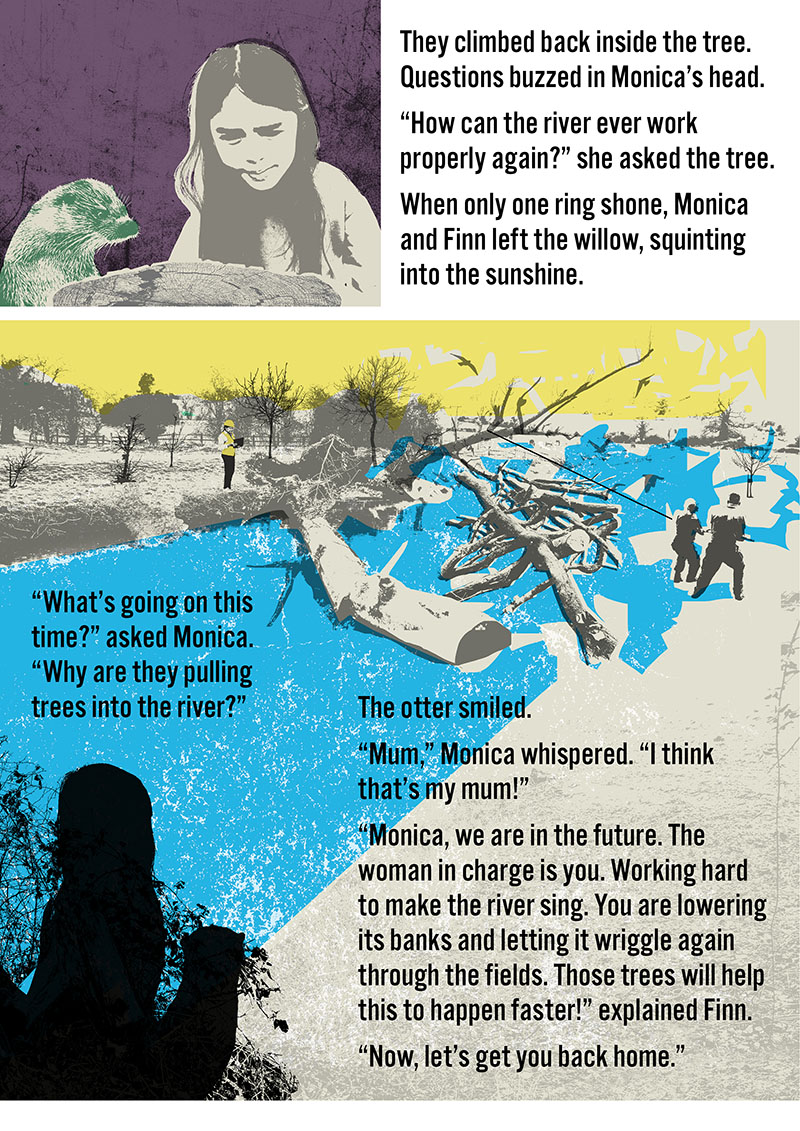

“How can the river ever work properly again?” she asked the tree.

When only one ring shone, Monica and Finn left the willow, squinting into the sunshine.

“What’s going on this time?” asked Monica. “Why are they pulling trees into the river?”

The otter smiled.

“Mum,” Monica whispered. “I think that’s my mum!”

“Monica, we are in the future. The woman in charge is you. Working hard to make the river sing. You are lowering its banks and letting it wriggle again through the fields. Those trees will help this to happen faster!” explained Finn.

“Now, let’s get you back home.”

“Goodbye, Finn,” she shouted.

“I’ve nearly finished cleaning up,” he said. “Give me a hand while you tell me about it.”

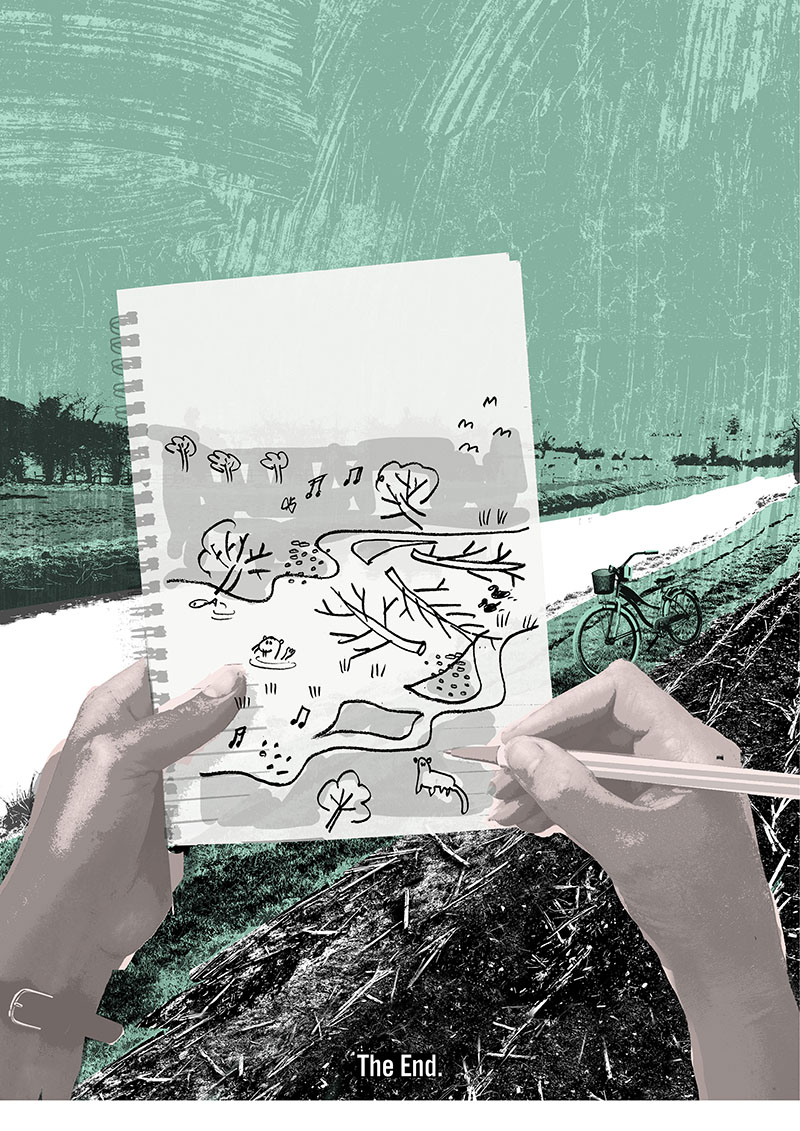

“It needs to roar and swoop and wriggle around corners and creep its way through the fields.

I’m going to make the river sing again!”

what is ‘nbs’ about this comic?

Rewilding rivers is like giving nature a makeover! By allowing rivers to flow naturally, we reduce flooding because the water spreads out more evenly. This process also restores farmland soils by depositing rich sediments, making the land more fertile. Plus, it’s fantastic for biodiversity. Natural river habitats support a variety of plants and animals, creating a thriving ecosystem. It’s a win-win for flood control, farming, and wildlife!

Title: The Sound of a River”. The title is based upon the saying that you “Can hear a healthy river” which is founded upon the idea that a healthy river should have a wide variation in flow pattern and dynamics, with a wide range of water sounds being generated by in-stream flow variation caused by water falling, changing speed and moving over or under obstacles such as stone or wood. In addition, the wide range of habitats created by the variety of flows in the river will increase biodiversity and so a listener will also hear the sound of the animals and plants living in or on the banks of the river, for example, insects, birds, fish, and mammals. Sounds could also be generated by the wind moving through bankside trees and vegetation. So, in general, the greater variety and volume of sound you can hear, the healthier and more natural the river.

Image 7: Many rivers have been significantly altered to make them straighter, by creating new channels and their banks have been raised to prevent water from flowing onto adjacent fields. Most of this is relatively recent engineering work, done to speed up the rate at which water can be drained from land to the sea and facilitate the draining of land for modern agriculture. High-raised banks are in most cases originally created using material taken from the river bed and have the effect of disconnecting a permanent area of the river (the channel) from the seasonal channel or floodplain. Trees have also often been removed or significantly reduced to make it easier to maintain the channel and to prevent them from changing the flows once they fall into the channel. A river in the condition as that in this image is not in its natural state and the response to high flows will be significantly different from what would happen in a pre-modified natural river. The physical shape and properties of a river are as important as water quality and flow in determining whether a stream or river is biodiverse and healthy.

Image 8: Willow trees are often associated with riparian (river banks) and wetland habitats and their roots can act to prevent erosion and stabilise banks. In some situations, where most other trees have been cleared, a few willows are left for this purpose and are managed by regular cutting to produce a distinctive shape. Left without intervention, willows will often spread easily and quickly, falling into rivers and streams, and can generate dynamic changes in direction and flow that add a range of habitat types to rivers. They are a valuable wetland tree, alongside alder.

Images 15 & 16: Larger-scale, intensive drainage and river engineering work historically began as soon as powered machines were able to change large areas of landscape in a relatively short period of time. Rivers were managed to increase flows and provide efficient drainage through landscapes. In many places, this is still the dominant paradigm for managing springs, streams, wetlands, and rivers. The reasons for this drainage work have often been to allow different and more intensive forms of agricultural production. Many floodplains are extremely fertile because they have been exposed to nutrients from river sediments over many thousands of years. Ironically, to take advantage of that fertility using modern farming techniques and equipment in many cases requires the protection of that land from further inundation, the separation of the channel from the floodplain, and the creation of a homogenous channel, resulting in significant wetland habitat loss and loss of river functionality, leading to declines in many plants, invertebrate, fish, bird, and mammal species. In addition, preventing floodplains from performing their natural function, means more water flowing at higher rates towards villages, towns, and cities, which can result in an increase in flood risk for those areas.

Image 21: A natural un-modified river will often occupy a large area of floodplain and include multiple threads or channels that change frequently in response to high flow events and the movement of sediments. Natural river systems often contain large quantities of living and dead wood, with smaller channels often having frequent log jams that will also drive dynamic physical changes in the channel. This variety of form and habitats, alongside large quantities of dead wood, means rivers and their associated wetlands are significant biodiversity hotspots. Rivers should be home to a large and diverse range of aquatic invertebrates, and aquatic mammals, in addition to fish and wetland bird species. High concentrations and abundance of plant and invertebrate biodiversity will attract a wide range of other bird and mammal species. Naturalised rivers will flow both within and outside their low flow channel, dependent upon rainfall, groundwater levels, and season. Floodplains tend to have higher rates of fertility, caused by the sediments carried from upstream which are deposited across the floodplain, and higher levels of moisture. Many farming techniques traditionally took advantage of the high fertility of floodplains, in some cases, even developing systems to artificially spread floodwaters through a pattern of fields. More modern farming systems, which use larger machinery and can increase fertility using artificially produced inorganic fertilisers, are not compatible with regular inundation, which is why rivers were and continue to be systematically re-engineered to prevent or reduce inundation. Some of the most fertile and easiest to work farmland can be found on floodplains. There is good evidence to show that re-connecting floodplains to river channels and restoring complexity and natural channels to rivers is a key mechanism for reducing flood risk to towns and cities.